Today kids we have a special guest post from Mitch Calvert a fitness pro from Canada and a regular on Breaking Muscle. He was kind enough to share some info with us today on seeing results in the gym….or lack of results for that matter. Check it out, enjoy and share any thoughts below….

Spinning Your Wheels In The Gym?

By Mitch Calvert www.mitchcalvert.com

Do you religiously go to the gym and hammer out one hard workout after the other without seeing the results you seek?

We’ve all seen the 160-pound soaking wet trainee who seemingly kills himself in the gym day-in and day-out, but his efforts to gain lean body mass are not being met.

Why is that? He may very well have drawn the short end of the stick in the genetics pool, but it’s just as likely there are errors in his ways outside of the gym. Hard training without the nutrition and rest to compensate will not yield optimal results.

One reason for the lack of results may lie directly with the management (or lack there of) of cortisol.

By definition, cortisol is a glucocorticoid, a steroid hormone released to ensure the brain has ample supply of glucose (sugar), its preferred fuel source in situations where simple survival is paramount. Cortisol can promote glycogen breakdown in skeletal muscle (i.e. muscle wasting) when preferable energy supply isn’t present. That’s bad news if you’re a bodybuilder or strength athlete looking to optimize lean body mass gains, get stronger and faster and so on.

The heavier and harder you work, the greater the cortisol release. If you don’t manage that cortisol release, you’ll literally be spinning your wheels and wasting hours of your time in the gym.

The Harder You Train…

A connection between too much cortisol and overtraining has been observed, subsequently in conjunction with a reduction in testosterone levels. (1-3)

Assuming most of you train hard, you can bet that each session you work out is substantially raising cortisol. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, as elevating cortisol was a significant predictor of lean body mass accumulation (4), so simply avoiding the gym altogether isn’t a better option! That’s not what I’m getting at here. You most definitely need to get the work in, but it’s how you manage that cortisol during and after the workout that’s the key.

The Cortisol Management Solution

So, how then, do you train with the necessary intensity to illicit the results you want while keeping cortisol at bay? A simple, no frills drink during your workout is the answer.

This isn’t particularly new information, but one study found 50 grams of pure carbohydrate (Gatorade) in a workout drink consumed during a resistance training (lifting weights) session completely eliminated cortisol elevations compared to a control flavored drink (5). Subjects within this particular study with the lowest cortisol – and the greatest muscle gains – were entirely from the group who drank the Gatorade. Whereas subjects tested with the highest cortisol showed the least gains (one placebo participant on the controlled drink even LOST muscle size during the study).

One logical reason for these results is the fact consuming carbs eliminates the need for gluconeogenesis to occur (conversion of protein to carbs, i.e. muscle breakdown for energy). Carbs are “muscle sparing” in this case, a readily available fuel source for your muscles during intense training. Without that supplementation, and once your storage of glycogen is eliminated, it stands to reason muscle protein breakdown will occur to fuel the remainder of the training session.

What should you do?

This is not to say you need to buy one of those “cutting edge” intra-workout supplements that are all the rage right now. No matter how the marketers spin the benefits of “high molecular weight” carbs etc., they all break down to glucose in the end. Some like to add amino acids (protein to the workout shake) but that’s personal preference too. If you have the cash, by all means go for it, cyclic dextrins are an expensive but highly effective option for your performance carbohydrate of choice, and branched-chain amino acids have some science backing their use. But a little Gatorade powder mixed in water will do the trick (reducing or eliminating cortisol) all the same if you’re on a budget. If the sugar upsets your stomach while working out, dilute in a liter or more of water. That solved the issue for me.

Then simply follow up your workout with a quality whole foods meal an hour or so after you’re done exercising like you normally would. You’ll recover faster and see more results than you would from that $200 stack the dude at GNC told you to buy. Don’t forget to manage outside stressors (life’s a B sometimes), which can impact cortisol just as much as hard training can, and get your sleep – that’s hugely important too.

Train smarter and reap the benefits.

Author Bio

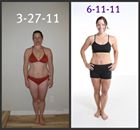

Mitch Calvert is a certified trainer specializing in the optimization of nutrition, exercise and health for athletes and Average Joes alike. Inspired by his own transformation as an obese teen to the fitness enthusiast he is today, Calvert now works to share his knowledge and expertise with his online clients looking to make a similar change in their lives.

Read more articles on his blog at www.mitchcalvert.com

SOURCES:

- Urhausen, A. and W. Kindermann, Diagnosis of overtraining: what tools do we have? Sports medicine, 2002. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11817995

- Fry, R.W., et al., Overtraining in athletes. An update. Sports medicine, 1991. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1925188

- Vogel, R., Übertraining: Begriffsklärungen, ätiologische Hypothesen, aktuelle Trends und methodische Limiten. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Sportmedizin und Sporttraumatologie 49 (4), 154–162, 2001, 2001. http://www.sgsm.ch/ssms_publication/file/85/4-2001-4.pdf

- West, D.W. and S.M. Phillips, Associations of exercise-induced hormone profiles and gains in strength and hypertrophy in a large cohort after weight training. European journal of applied physiology, 2012. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22105707

- Tarpenning, K.M., et al., Influence of weight training exercise and modification of hormonal response on skeletal muscle growth. J Sci Med Sport, 2001.